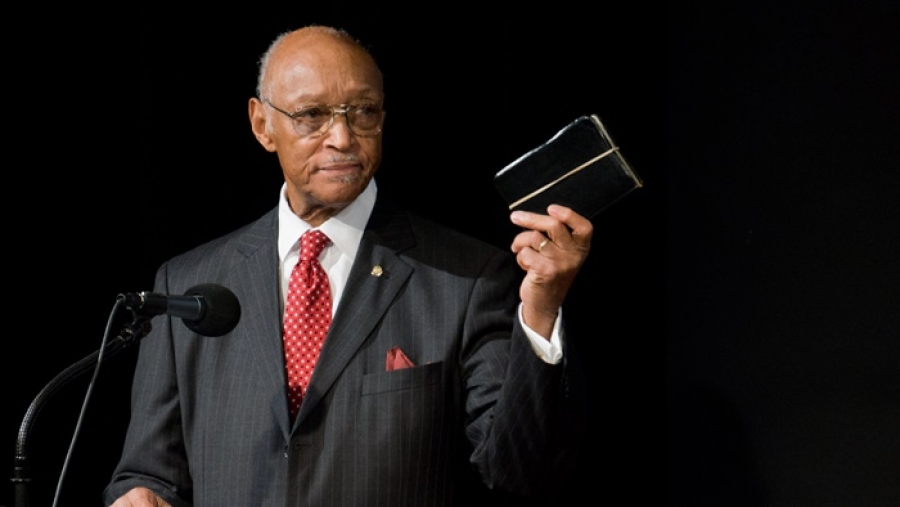

Preacher James Earl Massey, whose pastoral cadence went out over radio waves and across dozens of seminary chapels during his seven decades in ministry, died Sunday at age 88.

Massey is remembered as one of the most influential voices in the Church of God movement—a holiness denomination with about a quarter-million adherents in North America—and a gifted communicator who earned the nickname the “prince of preachers.”

“The Church of God (and many others) mourn the passing of one of our greatest voices, James Earl Massey,” tweeted Jim Lyon, general director of the Anderson, Indiana-based Church of God Ministries. “He walked through this world with exceptional grace, strength, and wisdom. Jesus was his preoccupation, the church was his friend, and the world was his stage.”

Massey taught and modeled Christ-centered, Scripture-centered preaching throughout his career, saying that “you can never master the art of preaching. It is always something toward which you are working, so that sermonizing is always a work in progress.”

After having served as senior pastor of the Metropolitan Church of God in Detroit, a speaker on the Christian Brotherhood Hour radio show, and pastor, professor, and dean at Anderson University, the late preacher became a distinguished elder-at-large for his denomination and dean emeritus at Anderson.

John S. Pistole, president of Anderson University, called Massey a “legend in the Church of God movement” who “impacted countless lives for Christ and the Kingdom.”

The Detroit native wrote 18 books on preaching and spiritual disciplines, and he lectured at over 100 colleges and seminaries, including Beeson Divinity School.

“Massey is the heir of a rich heritage of faith. … He was spiritually formed by Wesleyan theology, the Holiness movement, and the African American tradition,” Beeson dean Timothy George wrote. “The rich spiritual resources of these cultural and church traditions have informed, and are still reflected in, Massey’s approach to ministry and preaching. But there is a sense in which he transcends them all. The quest for authentic Christian unity is a major motif that runs deep through all of Massey’s ministry; his work has been at once both evangelical and ecumenical.”

In his preaching, he regularly quoted civil rights leaders like his colleague Martin Luther King Jr. and mentor Howard Thurman and cited them as inspiring his willingness to partner across denominational lines. He emphasized the Christ-centeredness of the African American preaching tradition as showcasing God as redeemer.

As a senior editor at Christianity Today, Massey wrote about the changing racial landscape of the US back in 1995:

Today a new historical moment is upon our churches to stand against attitudes that polarize and demonize. The church is armed with valid ethical claims and the means to deal positively with a diverse population that challenges those still tainted by the heresy that race and skin color is a measure of human worth. The quest for a reasoned Christian approach to our nation’s needs might be long and costly, but it will lead to our salvation as a people.

Two years ago, he celebrated the 70th anniversary of the first sermon he preached, when he suddenly heard God call him to the pulpit at age 16. “Since that time of encounter during worship, I have known the work to which my head, heart, and hands were to be devoted,” he wrote in his biography, Aspects of My Pilgrimage.

Massey held a bachelor’s degree from William Tyndale College, masters from Oberlin Graduate School of Theology, and doctorate from Asbury Theological Seminary. He was also a classical pianist and military veteran, having served as a chaplain’s assistant.

About a decade ago, the denominational leader and homiletics scholar was asked what he would preach about in his final sermon. Massey chose 1 Timothy 1:12–17, which begins, “I thank Christ Jesus our Lord, who has given me strength, that he considered me trustworthy, appointing me to his service.”

“That is the text I would use because Christ is first and foremost and last in my life,” he said. “I wouldn’t have been in the ministry if it hadn’t been for him.”

By KATE SHELLNUTT